A study of tracking cookies running on government and public sector health websites in the European Union has found commercial adtech to be operating pervasively even in what should be core not-for-profit corners of the Internet.

The researchers used searches including queries related to HIV, mental health, pregnancy, alcoholism and cancer to examine how frequently European Internet users are tracked when accessing national health service webpages to look for publicly funded information about sensitive concerns.

The study also found that most EU government websites have commercial trackers embedded on them, with 89 per cent of official government websites found to contain third party ad tracking technology.

The research was carried out by Cookiebot using its own cookie scanning technology to examine trackers on public sector websites, scanning 184,683 pages on all 28 EU main government websites.

Only the Spanish, German and the Dutch websites were found not to contain any commercial trackers.

The highest number of tracking companies were present on the websites of the French (52), Latvian (27), Belgian (19) and Greek (18) governments.

The researchers also ran a sub-set of 15 health-related queries across six EU countries (UK, Ireland, Spain, France, Italy and Germany) to identify relevant landing pages hosted on the websites of the corresponding national health service — going on to count and identify tracking domains operating on the landing pages.

Overall, they found a majority (52 per cent) of landing pages on the national health services of the six EU countries contained third party trackers.

Broken down by market, the Irish health service ranked worst — with 73 per cent of landing pages containing trackers.

While the UK, Spain, France and Italy had trackers on 60 per cent, 53 per cent, 47 per cent and 47 per cent of landing pages, respectively.

Germany ranked lowest of the six, yet they still found a third of the health service landing pages contained trackers.

Searches on publicly funded health service sites being compromised by the presence of adtech suggests highly sensitive inferences could be being made about web users by the commercial companies behind the trackers.

Cookiebot found a very long list of companies involved — flagging for example how 63 companies were monitoring a single German webpage about maternity leave; and 21 different companies were monitoring a single French webpage about abortion.

“Vulnerable citizens who seek official health advice are shown to be suffering sensitive personal data leakage,” it writes in the report. “Their behaviour on these sites can be used to infer sensitive facts about their health condition and life situation. This data will be processed and often resold by the ad tech industry, and is likely to be used to target ads, and potentially affect economic outcomes, such as insurance risk scores.”

“These citizens have no clear way to prevent this leakage, understand where their data is sent, or to correct or delete the data,” it warns.

It’s worth noting that Cookiebot and its parent company Cybot’s core business is related to selling EU data protection compliance services. So it’s not without its own commercial interests here. Though there’s no doubting the underlying adtech sprawl the report flags.

Where there’s some fuzziness is around exactly what these trackers are doing, as some could be used for benign site functions like website analytics.

Albeit, if/when the owner of the freebie analytics services in question is also adtech giant Google that still may not feel reassuring, from a privacy point of view.

100+ firms tracking EU public sector site users

Across both government and health service websites, Cookiebot says it identified a total of 112 companies using trackers that send data to a total of 131 third party tracking domains.

It also found 10 companies which actively masked their identity — with no website hosted at their tracking domains, and domain ownership (WHOIS) records hidden by domain privacy services, meaning they could not be identified. That’s obviously of concern.

Here’s the table of identified tracking companies — which, disclosure alert, includes AOL and Yahoo which are owned by TechCrunch’s parent company, Verizon.

Adtech giants Google and Facebook are also among adtech companies tracking users across government and health service websites, along with a few other well known tech names — such as Oracle, Microsoft and Twitter.

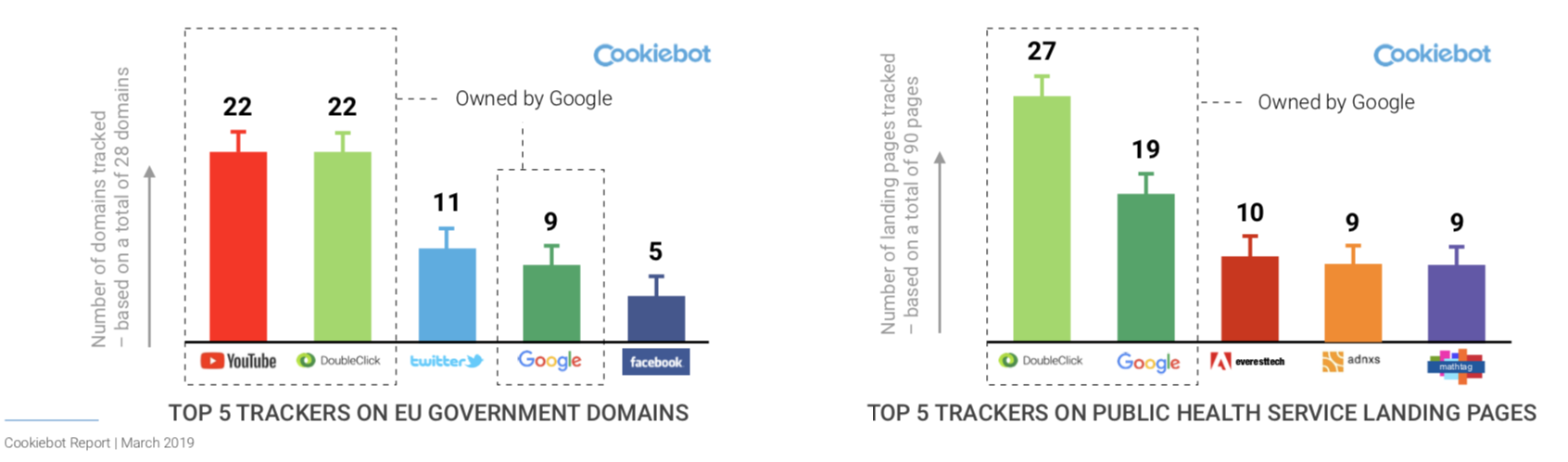

Cookiebot’s study names Google “the kingpin of tracking” — finding the company performed more than twice as much tracking as any other, seemingly as a result of Google owning several of the most dominant ad tracking domains.

Google-owned YouTube.com, DoubleClick.net and Google.com were the top three tracking domains IDed by the study.

“Through the combination of these domains, Google tracks website visits to 82% of the EU’s main government websites,” Cookiebot writes. “On each of the 22 main government websites on which YouTube videos have been installed, YouTube has automatically loaded a tracker from DoubleClick.net (Google’s primary ad serving domain). Using DoubleClick.net and Google.com, Google tracks visits to 43% of the scanned health service landing pages.”

“Given its control of many of the Internet’s top platforms (Google Analytics, Maps, YouTube, etc.), it is no surprise that Google has greater success at gaining tracking access to more webpages than anyone else,” it continues. “It is of special concern that Google is capable of cross-referencing its trackers with its 1st party account details from popular consumer-oriented services such as Google Mail, Search, and Android apps (to name a few) to easily associate web activity with the identities of real people.”

Under European data protection law “subjective” information that’s associated with an individual — such as opinions or assessments — is absolutely considered personal data.

So tracker-fuelled inferences being made about site visitors are subject to EU data protection law — which has even more strict rules around the processing of sensitive categories of information like health data.

That in turn suggests that any adtech companies doing third-party-tracking of Internet users and linking sensitive health queries to individual identities would need explicit user consent to do so.

The presence of adtech trackers on sensitive health data pages certainly raises plenty of questions.

We asked Google for a response to the Cookiebot report, and a spokesperson sent us the following statement regarding sensitive category data specifically — in which it claims: “We do not permit publishers to use our technology to collect or build targeting lists based on users’ sensitive information, including health conditions like pregnancy or HIV.”

Google also claims it does not itself infer sensitive user interest categories.

Furthermore it said its policies for personalized ads prohibit its advertisers from collecting or using sensitive interest categories to target users. (Though saying you’re telling someone not to do something is not the same as that thing not being done. That would depend on the enforcement.)

Google’s spokesperson was also keen to point to its EU user consent policy — where it says it requires site owners that use its services to ensure they have correct disclosures and consents for personalised ads and cookies from European end users.

The company warns it may suspend or terminate a site’s use of its services if they have not obtained the right disclosures and consents. It adds there’s no exception for government sites.

On tags and disclosure generally, the Google spokesperson provided the following comment: “Our policies are clear: If website publishers choose to use Google web or advertising products, they must obtain consent for cookies associated with those products.”

Where Google Analytics cookies are concerned, Google said traffic data is only collected and processed per instructions it receives from site owners and publishers — further emphasizing that such data would not be used for ads or Google purposes without authorization from the website owner or publisher.

Albeit sloppy implementations of freebie Google tools by resource-strapped public sector site administrators might make such authorizations all too easy to unintentionally enable.

So, tl;dr — as Google tells it — the onus for privacy compliance is on the public sector websites themselves.

Though given the complex and opaque mesh of technology that’s grown up sheltering under the modern ‘adtech’ umbrella, opting out of this network’s clutches entirely may be rather easier said than done.

Cookiebot’s founder, Daniel Johannsen, makes a similar point to Google’s in the report intro, writing: “Although the governments presumably do not control or benefit from the documented data collection, they still allow the safety and privacy of their citizens to be compromised within the confines of their digital domains — in violation of the laws that they have themselves put in place.”

“More than nine months into the GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation], a trillion-dollar industry is continuing to systematically monitor the online activity of EU citizens, often with the unintentional assistance of the very governments that should be regulating it,” he adds, calling for public sector bodies to “lead by example – at a minimum by shutting down any digital rights infringements that they are facilitating on their own websites”.

“The fact that so many public sector websites have failed to protect themselves and their visitors against the inventive methods of the tracking industry clearly demonstrates the educational challenge that the wider web faces: How can any organisation live up to its GDPR and ePrivacy obligations if it does not control unauthorised tracking actors accessing their website?”

Trackers creeping in by the backdoor

On the “inventive methods” front, the report flags how third party javascript technologies — used by websites for functions like video players, social sharing widgets, web analytics, galleries and comments sections — can offer a particularly sneaky route for trackers to be smuggled into sites and apps by the ‘backdoor’.

Cookiebot gives the example of social sharing tool, ShareThis, which automatically adds buttons to each webpage to make it easy for visitors to share information across social media platforms.

The ShareThis social plugin is used by Ireland’s public health service, the Health Service Executive (HSE). And there Cookiebot found it releases trackers from more than 20 ad tech companies into every webpage it is installed on.

“By analysing web pages on HSE.ie, we found that ShareThis loads 25 other trackers, which track users without permission,” it writes. “This result was confirmed on pages linked from search queries for “mortality rates of cancer patients” and “symptoms of postpartum depression”.”

“Although website operators like the HSE do control which 3rd parties (like ShareThis) they add to their websites, they have no direct control over what additional “4th parties” those 3rd parties might smuggle in,” it warns.

We’ve reached out to ShareThis for a response.

Another example flagged by the report is what Cookiebot dubs “YouTube’s Tracking Cover-Up”.

Here it says it found that even when a website has enabled YouTube’s so-called “Privacy-enhanced Mode”, in a bid to limit its ability to track site users, the mode “currently stores an identifier named “yt-remote-device -id” in the web browser’s “Local Storage”” which Cookiebot found “allows tracking to continue regardless of whether users click, watch, or in any other way interact with a video – contrary to Google’s claims”.

“Rather than disabling tracking, “privacy-enhanced mode” seems to cover it up,” they claim.

Google did not provide an on the record comment regarding that portion of the report.

Instead the company sent some background information about “privacy-enhanced mode” — though its points did not engage at all with Cookiebot’s claim that tracking continues regardless of whether a user watches or interacts with a video in any way.

Overall, Google’s main point of rebuttal vis-a-vis the report’s conclusion — i.e. that even on public sector sites surveillance capitalism is carrying on business as usual — is that not all cookies and pixels are ad trackers. So it’s claim is a cookie ‘signal’ might just be harmless background ‘noise’.

(In additional background comments Google suggested that if a website is running an advertising campaign using its services — which presumably might be possible in a public sector scenario if an embedded YouTube video contains an ad (for example) — then an advertising cookie could be a conversion pixel used (only) to measure the effectiveness of the ad, rather than to track a user for ad targeting.

For DoubleClick cookies on websites in general, Google told us this type of cookie would only appear if the website specifically signed up with its ad services or another vendor which uses its ad services.

It further claimed it does not embed tracking pixels on random pages or via Google Analytics with Doubleclick cookies.)

The problem here is the lack of opacity in the adtech industry which requires users to take ad targeters at their word — and trust that an adtech giant like Google, which makes pots of money off of tracking web users to target them with ads, has nonetheless built perfectly privacy-respecting, non-leaky infrastructure that operates 100% as separately and cleanly as claimed, even as the entire adtech industry’s business incentives are pushing in the opposite direction.

Also a problem: Certain adtech giants having a long and storied history of bundling purposes for user data and manipulating consent in privacy-hostile ways.

And with trust in adtech at such a historic low — plus regulation having been rebooted in Europe to put the focus on enforcement (which is encouraging a cottage industry of GDPR ‘compliance’ services to wade in) — the industry’s preferred cloak of complex opacity is under attack on multiple front (including from policymakers) and does look to be on borrowed time.

And as more light shines in and risk steps up, sensitive public sector websites could just decide to nix using any of these freebie plugins.

In another “inventive” case study highlighted by the report, Cookiebot writes that it documented instances of Facebook using a first party cookie workaround for Safari’s intelligent tracker blocking system to harvest user data on two Irish and UK health landing pages.

So even though Apple’s browser natively purges third party cookies to enhance user privacy by default Facebook’s engineers appear to have managed to create a workaround.

Cookiebot says this works by Facebook’s new first party cookie — “_fbp” — storing a unique user ID that’s then forwarded as a URL parameter in the pixel tracker “tr” to Facebook.com — “thus allowing Facebook to track users after all”, i.e. despite Safari’s best efforts to prevent pervasive third party tracking.

“In our study, this combined tracking practice was documented on 2 Irish and UK landing pages featuring health information about HIV and mental illness,” it writes. “These types of workarounds of browser tracking prevention are highly intrusive as they undermine users’ attempts to protect their personal data – even when using browsers and extensions with the most advanced protection settings.”

Reached for a response to the Cookiebot report Facebook also did not engage with the case study of its Safari third party cookie workaround.

Instead, a spokesman sent us the following line: “[Cookiebot’s] investigation highlights websites that have chosen to use Facebook’s Business Tools — for example, the Like and Share buttons, or the Facebook pixel. Our Business Tools help websites and apps grow their communities or better understand how people use their services. For example, we could tell them that their site is most popular among people aged 20-25.”

In further information provided to us on background the company confirmed that data it receives from websites can be used for enhancing ad targeting on Facebook. (It said Facebook users can switch off ad personalization based on such signals — via the “Ads Based on Data from Partners” setting in Ad Preferences.)

It also said organizations that make use of its tools are subject to its Business Tools terms — which Facebook said require them to provide users with notice and obtain any required legal consent, including being clear with users about any information they share with it.

Facebook further claimed it prohibits apps and websites from sending it sensitive data — saying it takes steps to detect and remove data that should not be shared with it.

ePrivacy Regulation needed to raise the bar

Commenting on the report in a statement, Diego Naranjo, senior policy advisor at digital rights group EDRi, called for European regulators to step up to defend citizens’ privacy.

“For the last 20 years, Europe has fought to regulate the sprawling chaos of data tracking. The GDPR is a historical attempt to bring the information economy in line with our core civil liberties, securing the same level of democratic control and trust online as we take for granted in our offline world. Yet, as this study has provided evidence of, nine months into the new regulation, online tracking remains as hidden, uncontrollable, and plentiful as ever,” he writes in the report. “We stress that it is the duty of regulators to ensure their citizens’ privacy.”

Naranjo also warned that another EU privacy regulation, the ePrivacy Regulation — which is intended to deal directly with tracking technologies — risks being watered down.

In the wake of GDPR it’s become the focus of major lobbying efforts, as we’ve reported before.

“One of the great added values of the ePrivacy Regulation is that it is meant to raise the bar for companies and other actors who want to track citizens’ behaviour on the Internet. Regrettably, now we are seeing signs of the ePrivacy Regulation becoming watered out, specifically in areas concerning “legitimate interest” and “consent”,” he warns.

“A watering down of the ePrivacy Regulation will open a Pandora’s box of more and more sharing, merging and reselling of personal data in huge online commercial surveillance networks, in which citizens are being unwittingly tracked and micro-targeted with commercial and political manipulation. Instead, the ePrivacy Regulation must set the bar high in line with the wishes of the European Parliament, securing that the privacy of our fellow citizens does not succumb to the dominion of the ad tech industry.”

No comments:

Post a Comment